A pitch is often the difference between a good idea that stalls and a good idea that gets funded, signed, or sold. In a few minutes, you are asking strangers to believe in your business, your numbers, and you as a leader—often with less time than it takes to drink a coffee. That is why the art of the pitch is not just about slides; it is about shaping a clear, confident story that makes people think, “This is worth backing.”

This article breaks down exactly how to craft and deliver a pitch that works. You'll learn a proven 8-step structure that works for investors, clients, banks, and partners, how to adapt it for different audiences, common mistakes to avoid, and practical tips for slides, delivery, and handling tough questions.

What a Great Pitch Actually Does

A pitch is not a data dump or a slide recital. Its job is to move your audience from uncertainty to belief.

A strong pitch should:

- Explain the problem you solve in a way that feels real and urgent.

- Show clearly how your solution is different and better.

- Prove that there is a credible market and business model.

- Build trust in you and your team as the people to execute.

- End with a specific, realistic ask.

Whether you are talking to investors, corporate buyers, banks, or potential partners, the core elements are similar. The emphasis changes, but the underlying structure remains remarkably consistent.

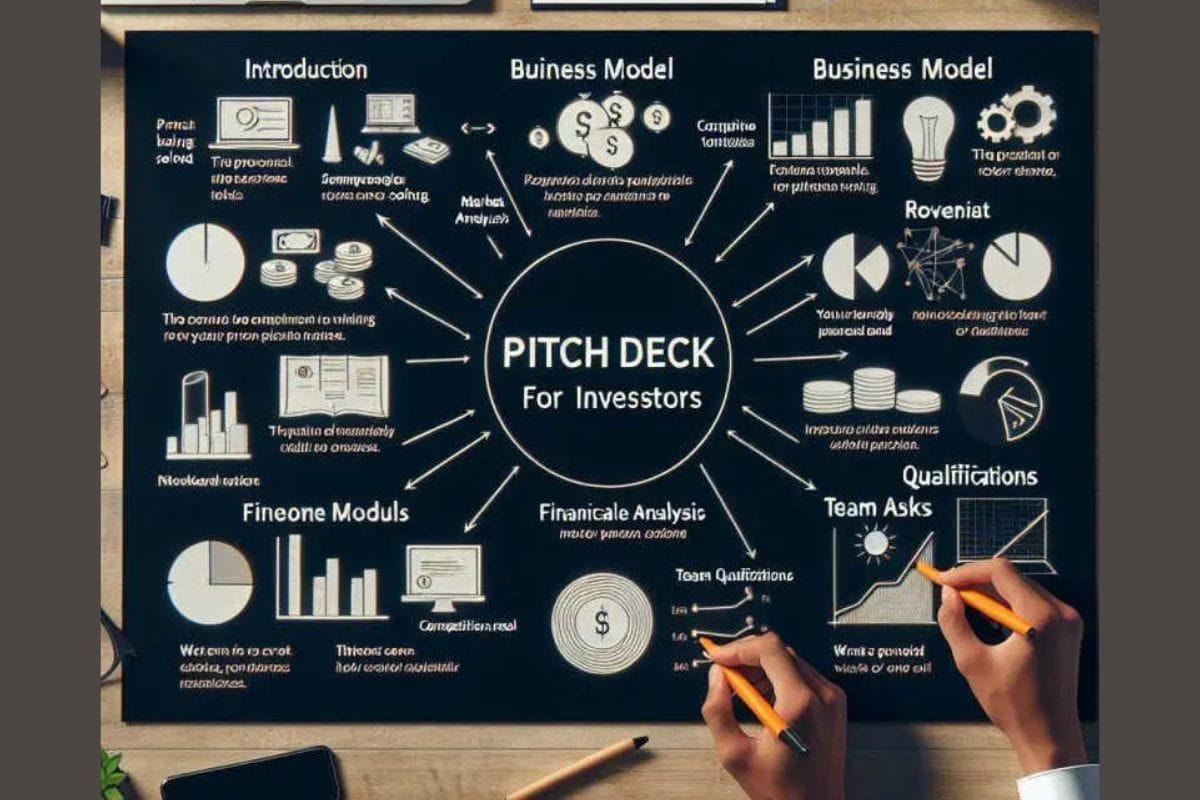

Structuring the Perfect Pitch

Think of your pitch as a story with a logical flow. A simple, reliable structure is:

- Hook

- Problem

- Solution

- Market and Business Model

- Traction and Proof

- Team

- The Ask

- Close

- Start with a Powerful Hook

People decide in seconds whether they are interested in what you are saying. Begin with something that grabs attention and frames the conversation.

You can do this by:

- Sharing a vivid customer scenario: “Every day, small retailers waste hours reconciling inventory by hand…”

- Using a surprising fact: “60% of SMEs still use spreadsheets as their main ‘system’ for finance and operations.”

- Asking a pointed question: “Have you ever lost a deal because your quote took too long?”

The hook should be short—one or two sentences—and set up the problem you are about to present.

- Define the Problem Clearly

If your audience does not believe the problem exists or matters, they will not care about your solution.

To describe the problem effectively:

- Focus on pain, not features: talk about time lost, money wasted, frustration, or risk.

- Be specific: “Restaurant managers in busy cities spend 8–10 hours weekly on manual scheduling.”

- Avoid jargon: speak in simple, concrete terms your audience immediately understands.

A good test: If you read the problem slide alone to someone in your target market, they should say, “Yes, that’s exactly what we go through.”

- Present Your Solution Simply

Once the problem is clear, show how you solve it—clearly, visibly, and without unnecessary complexity.

Answer these questions:

- What does your product or service actually do?

- How does it address the problem better than the status quo?

- What is your core value proposition in one sentence?

Use plain language. Instead of saying “AI-powered omnichannel engagement platform,” say “We help small businesses reply to all customer messages—from WhatsApp, email and social—in one place, automatically.”

Visuals help: show a simple diagram or before/after scenario:

- Before: multiple tools, manual work, missed messages.

- After: one interface, automation, faster response.

- Show the Market and Business Model

Now that the audience understands what you do, they need to know if it can become (or already is) a real business.

Cover:

- Who your target customers are (not “everyone”). Be as specific as possible.

- The size and growth potential of the market segment you actually serve.

- How you make money: pricing model, typical deal size, and repeat revenue potential.

Investors want to see that you are focused enough to win a niche, yet that the niche is large or expandable enough to matter. Corporate buyers want to know you understand their segment. Both want to see a clear path to sustainable revenue.

- Provide Traction and Proof

Claims are easy; evidence builds trust. This is where you show that the business works in the real world.

Traction can be:

- Revenue numbers and growth trends.

- Number of active users or customers.

- Retention and repeat purchase behaviour.

- Key partnerships or pilot programmes.

- Case studies or testimonials.

If you are early stage, share whatever proof you have:

- Early pilot results.

- Strong letters of intent.

- Waitlists or pre-orders.

Rather than drowning the audience in numbers, select 3–5 metrics that best show momentum and alignment with your strategy.

- Highlight the Team

Many decisions are ultimately bets on people. Your audience needs to see why you are the right person (and team) to execute this vision.

Focus on:

- Relevant experience (industry, problem domain, technology).

- Past wins (exits, major projects, successful launches).

- Complementary skills within the founding or leadership team.

You do not need to list every job you have had. Instead, connect your background to the problem: “I ran a logistics company for 10 years and saw first-hand the cost of manual routing, which led me to build this solution.”

- Make a Clear, Concrete Ask

A pitch must lead somewhere. Avoid vague endings like “So that’s our story—any questions?”

Instead, be specific:

- If you are pitching investors: “We are raising X to achieve Y in Z months—specifically, to hire, expand, or launch.”

- If you are pitching a corporate buyer: “We would like to start with a 3-month pilot in two branches, with these KPIs.”

- If you are pitching a bank: “We are requesting a facility of X to fund inventory and marketing for the next season.”

A clear ask signals confidence and helps your audience respond meaningfully.

- Close with Vision and Confidence

End on a note that reconnects to your larger vision:

- What will be true in 3–5 years if you succeed?

- What impact will you have on customers, the market, or the region?

This is where you zoom back out from operational details to the bigger picture: “If we execute, we will become the default back office for independent restaurants in the region.”

Crafting Different Pitches for Different Audiences

Although the core story stays similar, your emphasis should shift depending on who you are pitching.

Investors

Investors care about:

- Market size and growth.

- Scalability of your model.

- Unit economics (how you make profit per customer).

- Team strength and defensibility (moats, differentiation).

Spend more time on market, traction, and economics. Be ready for detailed questions on assumptions, margins, and runway.

Corporate Clients or Partners

Corporate buyers want:

- Reliability and risk mitigation.

- Fit with their existing systems and processes.

- Clear ROI (cost savings, revenue uplift, brand value).

- Implementation speed and support.

Emphasise case studies, integration, support structure, and risk management. Show that working with you is safe and worthwhile.

Banks and Lenders

Lenders focus on:

- Cash flow stability.

- Collateral and guarantees.

- Track record.

- Risk of default.

Present conservative projections, evidence of disciplined management, and clear repayment capacity. This is not the moment for wildly optimistic hockey-stick charts.

Customers (Sales Pitches)

Customers care about:

- Their specific problem.

- Outcomes: saving time, making money, reducing risk, improving status.

- Ease of adoption.

- Price versus perceived value.

Keep it simple and customer-centric. Less about your long-term vision, more about “what this does for you this quarter.”

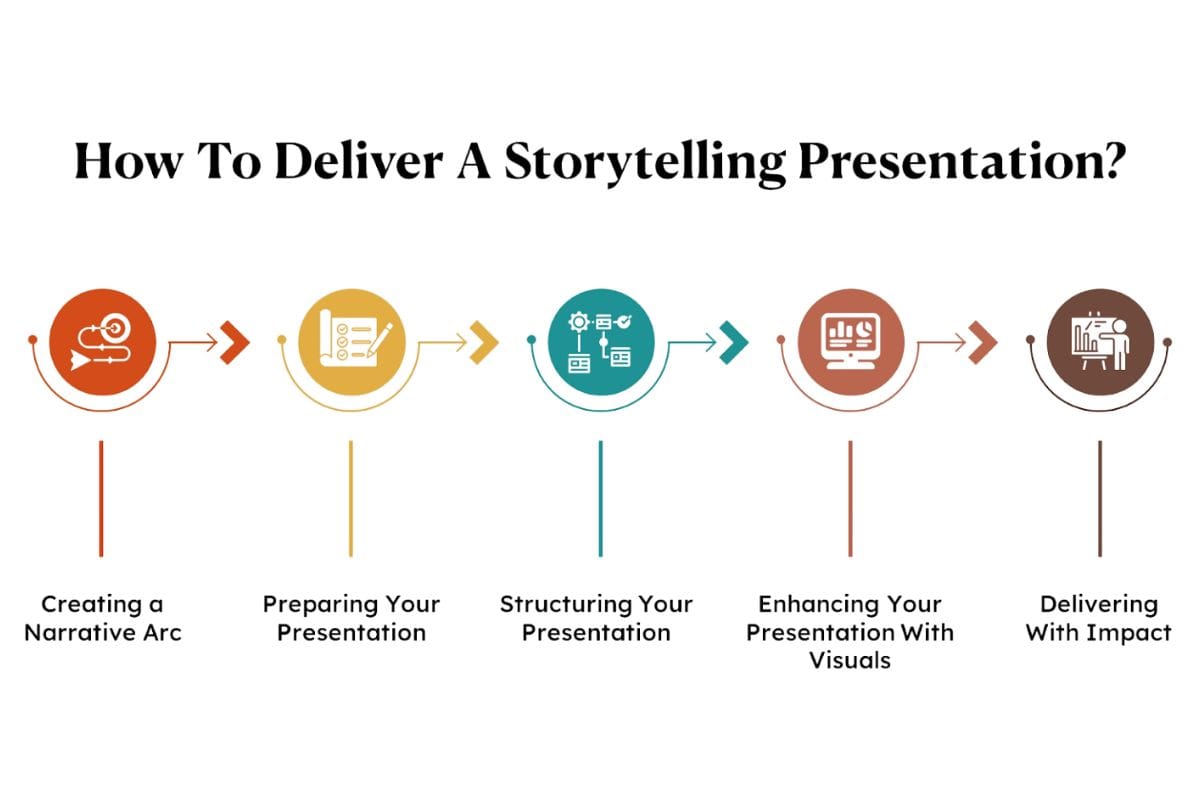

The Role of Storytelling and Emotion

Data matters, but people remember stories. Storytelling is not fluff; it is how humans process information.

Use:

- A customer anecdote that illustrates the problem and your solution.

- Your own founder story—what pushed you to start this company.

- Clear before/after narratives.

The key is authenticity. Over-polished, dramatic narratives that feel exaggerated can hurt credibility. Simple, honest stories are far more effective.

Slides and Visuals: Support, Don’t Suffocate

Slides are there to support your verbal pitch, not replace it.

Good slide practices:

- One main idea per slide.

- Minimal text; use bullet points and headlines.

- Clear charts, not cluttered dashboards.

- Visuals that make complex ideas intuitive (e.g., process diagrams, simple graphs).

Bad practices:

- Reading slides word-for-word.

- Tiny fonts and walls of text.

- Unnecessary animations and gimmicks.

Ask yourself: could someone understand the rough story by flipping through your deck in 3 minutes? That is often how busy investors review decks initially.

Delivering the Pitch: Presence and Practice

How you say things matters as much as what you say.

Key delivery principles:

- Practice out loud multiple times; refine based on what feels clumsy.

- Aim for a natural, conversational tone—not memorised scripts or robotic reading.

- Maintain eye contact and open body language.

- Control your pace: not so fast that people get lost, not so slow that they drift.

Time discipline is critical. If you are given 10 minutes, plan for 8–9 and leave space for questions. Going over time signals poor preparation and respect for the audience.

Handling Questions and Objections

Q&A often reveals more about you than the prepared pitch.

To handle questions well:

- Listen fully before answering; do not interrupt.

- It is acceptable to say “I don’t know yet—but here is how we are thinking about it.”

- If a question exposes a weakness, acknowledge it and explain your plan to address it.

- If someone is challenging, stay calm and professional; others are as interested in how you respond as in the content.

Prepare for predictable questions:

- How will you acquire customers?

- What stops a larger competitor from copying you?

- What happens if your assumptions are wrong?

- How will you use the funds?

- What are your biggest risks?

Having clear, honest answers here boosts confidence in your leadership.

Common Pitch Mistakes to Avoid

Founders often fall into the same traps:

- Overloading with technical detail and under-explaining the actual business.

- Being vague about the target customer (“everyone with a phone”).

- Hiding weaknesses instead of owning them.

- Using buzzwords instead of plain language.

- Forgetting the ask or making it ambiguous.

A useful discipline is to have someone outside your industry listen to your pitch and tell you what they understood. If they cannot explain your business in one or two sentences, it is not yet clear enough.

Building and Refining Your Pitch Over Time

Your pitch is not a one-time project. It evolves as your business grows, your market shifts, and you learn what resonates.

Helpful habits:

- After each pitch, jot down what landed, what confused people, and what questions kept recurring.

- Treat their questions as free consulting: if people are always confused by one part, fix that slide or explanation.

- Keep a “living” version of your deck and a shorter “teaser” version for email introductions.

Ultimately, the art of the pitch is the art of clear thinking. When you can express your business simply and convincingly under time pressure, it is usually because you have done the hard internal work of understanding it deeply yourself. That clarity is what your audience is really buying into—along with your ability to execute on the story you just told.

Also Read: